A Howard University professor and her colleagues wax philosophical about one of the biggest buzzwords in science.

Scientific meetings are often stiff, stuffy affairs. The Gordon Research Conferences, however, are a refreshing exception. Billed as forums for “the presentation and discussion of frontier research,” Gordon conferences seek to create intimate, informal settings for talking about big scientific questions. To encourage participants to loosen their inhibitions, talks are typically off the record. Plus, afternoons are kept free of presentations, to leave room for informal interactions and networking.

Each of the dozens of Gordon conferences held each year tackles a single, often esoteric, topic. At the June 2013 conference at the Snowflake Resort in Stowe, Vermont, that topic was environmental nanotechnology — essentially, the science of very tiny things. Roughly speaking, a nanostructure is to a speck of dust as a person is to the Empire State building.

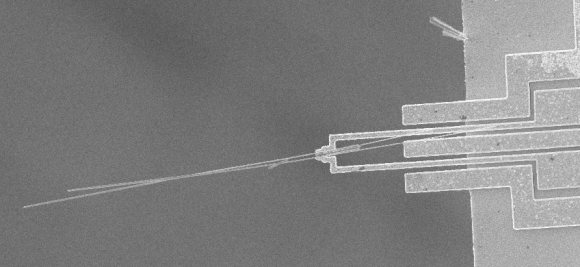

Scientists have come up with several strategies for building those structures, including etching a surface with chemicals and lasers and even tailoring designer molecules that can assemble themselves. Though they’re far too small to see with the naked eye, nanostructures impact our everyday life: They can be used to deliver cancer drugs to the site of a tumor, detect chemical weapons and pollutants, store computer data, and much more. But are they really all that new?

That question was the subject of a debate at the Gordon Conference in Stowe. I wasn’t there, but a recap recently published in the journal Environmental Science: Nano gives the tale of the tape. It’s a fascinating glimpse into the proceedings of a conference that usually keeps its talks under wraps. Michael Hochella of Virginia Tech University argued that the magic of nanomaterials is not new—that Nature has been “playing these tricks for billions of years.” Michael Spencer of Cornell argued the counterpoint. Howard University’s Kimberly Jones led the discussion.

The debate isn’t moot. If manmade nanomaterials really aren’t distinguishable from Mother Nature’s, maybe we needn’t be so concerned about their potential deleterious effects on our health. And maybe Nature can show us new and better ways to make them.

Hochella’s argument is buttressed by an abundance of evidence of natural nanomaterials. “The 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Robert F. Curl Jr., Sir Harold Kroto, and Richard E. Smalley for the discovery of fullerenes,” he says, but since that discovery natural versions of the soccer-ball shaped molecules “have been found in everything from soot to deep space.” He also cites other natural nanostructures, including nanodiamonds found in meteorites; organic nanomaterials formed in the dust clouds of infant stars:

The naturally-occurring nanomaterials that we have observed to date exhibit an astounding range of variety and complexity…In contrast, the current estimates of the annual manmade production of high-tonnage nanomaterials [are] roughly five to six orders of magnitude less than Nature’s bounty, and by comparison, limited in compositional and structural variation.

Spencer, on the other hand, argures that manmade nanomaterials are fundamentally different from Nature’s:

Manmade nanomaterials distinguish themselves from natural materials through several properties, [including] order, purity, and scale. Whether it is the ability of engineered nanomaterials to maintain order or identically reproduce large quantities of material scale, these are properties that [Natural] materials often do not have.

As an example, he points to the role of silicon technology in modern computing:

In addition to the mechanical perfection, the silicon used in the semiconductor industry has almost a complete absence of unintentional impurities in the crystal…There is no analog of this type of material’s foundry in Nature, no place on the earth where it is possible to go with a pick axe and slice off a bit [of] material on which to produce a microprocessor.

Unsurprisingly, the debate concludes in conciliatory fashion, with an eye toward future work:

When determining whether [environmental nanomaterials] are truly novel or not, one must realize that we have only just begun to interrogate the Earth’s surface and atmosphere for evidence of these structures…. At some point, the discovery of naturally-occurring nanomaterials may converge with new ENMs, but in the meantime, scientists and engineers must work together to increase the speed of discovery on both sides of the debate.

One thought on “Is nano even new?”